Understanding distress behaviour, brain responses and the importance of regulation

Information

Here you’ll find answers to some common questions concerning distressing behaviour.

Select the underlined questions below to see more.

The term ‘behaviour’ is just how we as humans act, it is our actions and the things we do. We as people can display distress behaviours as a result of feeling stressed/ distressed. Behaviour is a communication. Sometimes, we might do or say things that we don’t mean when we are feeling overwhelmed or stressed. This is our stress response system, we might start to feel the physiological changes in our bodies, and we might start to experience the fight/ flight responses.

Children and young people who are neurodivergent (including learning disabilities, learning difficulties, Autism, ADHD etc.) might struggle to communicate their distress to others, they might be experiencing the fight/ flight responses due to the changes in their brain and become out of control of their actions.

Some previous terms of behaviour were phrased as ‘challenging behaviour’ or ‘problem behaviour’. It is important that we move away from these terms as these lead us to portray the behaviour as challenging to us or that it is a problem/ naughty or difficult. This way of thinking is putting the blame on the child/ young person. If we start to think that behaviour is communicating distress, we stop looking at the behaviour as challenging us. If we understand what happens in a person’s brain when they are in distress, we can view and respond to those behaviours of communication as a result of distress more effectively and with empathy.

A helpful way to understand why someone might be displaying distress behaviours, is to understand what the ‘I statement’ is. If you can highlight a possible ‘I statement’ you can understand the function and how to respond in a more effective way to reduce distress in this incident but also for future experiences.

Distress behaviours can be displayed as a result of many types of stress/ distress. Some possible ‘I statements’ can include:

- I am experiencing pain

- I do not like this

- I want to leave

- I find this overwhelming or uncomfortable

- I am bored

- I am hungry

- I need your help

- I want you to play

- I want you to interact/spend some time with me

- I need sensory feedback such as pressure, climbing, spinning, jumping.

- I want to do this

- I want more

References – Understanding Behaviour and its Risks. CPI Safety Intervention TM. (2024.). Available at: https://cdn.crisisprevention.com/resources/instructor-guides-and-presentations/ROW/safety-intervention-3rd-edition-foundation-for-children-and-young-people/course-guides/PDF_SIF_3E_Youth_IG.pdf?_gl=1 [Accessed 7 Feb. 2025].

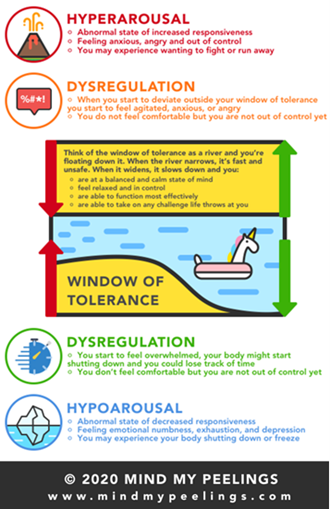

Window of Tolerance

The window of tolerance is our optimal zone when we feel safe, happy and in control.

Frequent stress and/ or trauma can cause us to leave our window of tolerance and causes us to feel dysregulated as our stress response activates. When this happens, our emotional brain can take over and we can go into a state of hyperarousal. This can cause us to react defensively, but this is because our fight/ flight response is kicking in and is trying to keep us safe. We can sometimes go into a state of hypoarousal when we shut down or ‘freeze’. This can happen when we feel dysregulated and overwhelmed.

Stress response system

When we encounter a stressful incident or situation, it can cause a stress-releasing hormone; this can then cause some physiological changes in our body that we might notice such as:

- Heart beating faster, you might feel it heavy and hear it loud in your ears/head.

- Your breathing might get faster and heavier, you might feel out of breath.

- You might feel sweaty or feel like you are shaking.

- Your muscles will tense, you might clench your fists/jaw.

Your brain passes signals (messages) to different parts of your brain for you to process and respond to. There are different responses include:

- Fight: you will feel the need to fight or physically respond to the threat/stress if you feel you can overcome it. This response helps to defend and protect us.

- Flight: if you don’t feel that you can overcome the threat, this response can include running away, escaping or hiding as a response to a threat.

- Freeze: this can mean that people will stop, they might appear in shock. Freeze can sometimes give the brain more time to evaluate next steps and then choose the best response.

- Fawn: this is where a person will try to appease or go along with what is happening.

- Flop: this is similar to ‘freeze’ but here you might see the person become limp or floppy or faint.

Stress and stressful situations can cause us to feel anxious, at this point we might have some control over the situation and our actions. We may then start to feel defensive as our body’s defence system takes over. The fight/flight response happens during this stage.

There are two states of dysregulation and they both impact your body and brains differently

- Hyper arousal (High)

This is where you can experience a heightened sense of anxiety, you might become more sensitive or overly responsive during this time period. Fight/Flight is present when you are feeling hyper aroused. Your senses particularly become very sensitive as you analyse your surroundings and events happening around you.

If you are feeling hyper aroused it can cause physiological challenges such as difficulties sleeping, managing emotions and digestive difficulties.

- Hypo arousal (Low)

This is where we might have a decrease in our responsiveness, similarly to hyper arousal it can impact on your sleep and ability to eat, understand, process and express emotions/thoughts.

Returning to the window of tolerance

It is very important to return to our optimal zone and understand what might be causing the window of tolerance to shrink and the reason for entering either hypo or hyper arousal. It is important to consider any feelings/emotions related to the behaviours. This will help you to identify the early warning signs of anxiety.

It is then important to understand the function of these emotions/feelings. This helps to understand the precipitating factors (triggers) for dysregulation. When you understand what the precipitating factors and function are for the feeling of dysregulation, you can then start to create a plan which helps you to adapt, make changes or avoid certain situations that cause stress/distress.

References for this section:

LeWine, H.E. (2024). Understanding the stress response. [online] Harvard Health. Available at: https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/understanding-the-stress-response.

Mind My Peelings. (2019). How to Recognize Your Window of Tolerance. [online] Available at: https://www.mindmypeelings.com/blog/window-of-tolerance

Co-regulation is the term used for someone supporting another person to regulate. This might be a parent/ carer supporting a child/ young person to regulate their emotions.

What about self-regulation? Self-regulation is formed from the basis of co-regulation. Children and young people are taught the skills of self-regulation through co-regulation which is why co-regulation is very important.

Co-regulation is about providing security, understanding, empathy and kindness to a child/young person to enable them to learn the skills to self-regulate.

There are three main categories of support that help children/ young people to develop their fundamental self-regulatory skills, these include:

- Providing a warm and responsive relationship

Nurturing with compassion, love and care. Providing a safe and responsible environment. Teaching children that their every action has a reaction that will be responded to (responding to cues and communication). Supporting children to communicate and express their needs/ wants in a positive way and this will help to create a safe and secure attachment.

Nurturing with compassion, love and care. Providing a safe and responsible environment. Teaching children that their every action has a reaction that will be responded to (responding to cues and communication). Supporting children to communicate and express their needs/ wants in a positive way and this will help to create a safe and secure attachment.

- Providing a structured and predictable environment and responses

Offering a structured environment will increase predictability which helps to decrease uncertainty and distress. It helps children to understand what is expected of them and how to act. They will also understand how other people are predicted to respond to them which provides a safe environment and ability to express. It will enable an environment where they can learn.

- Teaching and role modelling self-regulation skills

When children/young people are in a safe and secure environment they are able to trust their care givers and their responses, it encourages them to seek comfort, help and support from parent/caregivers. They can then be supported to co-regulate to calm and make sense of and manage their emotions.

Co-regulation is extremely important in supporting children and young people to build their own self-regulation skills/techniques. With effective co-regulation children/young people will have their needs met and the adult providing the co-regulation will become a trusted adult or a safe base for their child. This will then help the child to feel relaxed, safe, confident and have higher self-esteem.

Co-regulation ideas: (see hand out for more information)

- Talk about emotions/feelings and label/ normalise these

- Practice slow breathing

- Walking, exercising and offering movement

- Listening to music

- Physical contact, hugging, reassurance

- Meeting sensory calming needs (rocking, swinging etc.)

References – Co-Regulation from Birth Through Young Adulthood: A Practice Brief. (2017). Available at: https://fpg.unc.edu/sites/fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/reports-and-policy-briefs/Co-RegulationFromBirthThroughYoungAdulthood.pdf.

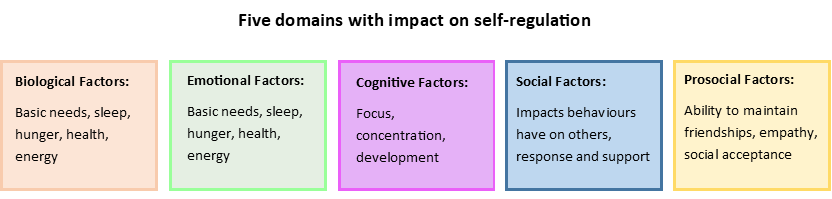

Self-regulation is associated with all humans and our ability to regulate our emotions and body as a result of our emotions and sensory feedback. Self-regulation begins in childhood and is related to the child’s ability to control their own thoughts, feeling and behaviours by themselves.

Self-regulation is formed from the basis of co-regulation and the support that was received during times of distress and experience of intense emotions.

Self-regulation involves the ability to:

- Understand your own behaviours and reactions

- Managing your emotions and reactions, these can include feeling angry, excited and anxious

- Being able to control impulses and not completing/ limiting impulsive actions

- Being able to calm down or remain calm after an incident that is particularly distressing or exciting

- Obtaining independence and being in control of your own actions

Children and young people with neurodiverse needs might struggle with self-regulating due to a number of different reasons. It is important that co-regulation is offered to support if this is the case.

Supporting people with self-regulation:

Supporting people with self-regulation:

- Discuss their emotions and behaviours when they are calm

- Consider activities to support self-regulation

- Plan for the future events and outcome of these

- Role modelling appropriate and desirable behaviours

- Debriefing after distressing incidents

- Suggest problem solving solutions

- Role playing is integral to support learning in a positive and safe way

- Identifying a safe space

References: Birth to 5 matters (2021). Self-regulation – Birth To 5 Matters. [online] Birth to 5 Matters. Available at: https://birthto5matters.org.uk/self-regulation/.

Berthiaume, L. (2023). Dr. Stuart Shanker’s 5 Domains of Self-Regulation. [online] The Montessori Room. Available at: https://themontessoriroom.com/blogs/montessori-tips/dr-stuart-shankers-5-domains-of-self-regulation?srsltid=AfmBOorMnKJMfVeDNkTFQ_kaa-Ldm2f15xPB1FZrz7ajSFgFL4ao62j- [Accessed 7 Feb. 2025].

Finding help

What can you do?

- Contact your GP or Paediatrician

Select the underlined topics below to view what resources are available.

Getting more help

If you haven’t already found the help you’re looking for, you can find additional information and services which are more interactive here.